I sometimes have the suspicion that cinema, when seen as art, has again become narrative; as if nothing had happened, as if there were no cinema history; or as if it had progressed in a linear fashion. Installations that deal with cinema often have a nostalgic flavour and thus create an unusual contradiction: by focusing on “back then”, they try not to strip courses of history of their linearity by spacialization, as one might expect from an installation; rather they try to represent them.

The difference between contemporary installations and the concept of expanded cinema as it existed in the 1960s and ‘70s is that one comes from the art world, the other from cinema. One tells something about cinema, while the other is cinema and speaks about itself. Perhaps one should regard Anne Quirynen’s work as an expanded cinema installation – or simply as a peepshow, the predecessor of cinema from the point of view of video.

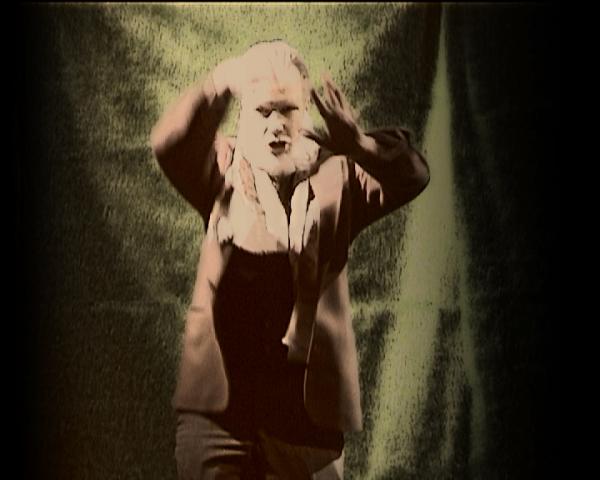

If film originates in the head of the viewer, as Alexander Kluge says, then that head is a structural component of film, a piece of architecture. To see Maximilian’s Darkroom, the viewer has to bend over and put his head in a box. That closes the back wall of the movie theater; the viewer’s face and the screen, of equal size, confront each other. One’s own gaze projects a film onto the screen. Maximilian’s Darkroom begins silently. Iacob has white hair and a long beard and dances, bent over. The image is black-and-white, the movement slow motion. The background is like a stage, as is familiar from the earliest movies, and the format of the picture is square.

“Stay in the costume and stay in the frame,” we read on a music hall poster or on the Website of the Berlin venue Ausland, that announces the performance “Cat Calendar” by and with Antonija Livingstone and Antonia Baehr. Their performance begins on stage and ends in a video installation. The viewer – his head still in the box – wonders how the rest of his body, below his head, must look to those who pass him to enter the real cinema he is in front of. But he can’t change his posture without destroying the architecture of his movie theater and missing the film, to boot. But has his shirt pulled out of his trousers as he’s bent over? Or is her skirt too short?

Iacob dances in the picture’s foreground. The Einstein wig takes up so much space that the teased hairdo sometimes extends outside the picture frame. But Iacob never dances out of the picture; Iacob dances as if trying to precisely measure the bounds of the video image: up, down, to the right and left– and diagonally. A two-dimensional surface as large as Iacob.

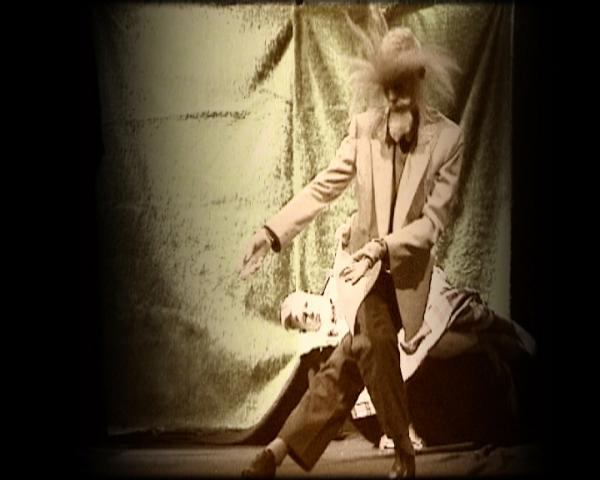

Iacob is old and weary. He steps all the way to the back of the stage and lies down on Fritz’s body, which is rolled up like a cat, too far to the right at the lower edge of the picture. Iacob rests there. The weight of the two threatens to topple the image.

“Never ask whether it likes to dance if you can’t dance yourself,” the poster continues further below.

Is my posture equally tilted?

On the screen, the stage-film-space opens wide. With a step outside, colours appear, glaring light, and the sounds of a scratched record; the fairy-tale forest plays dance music from the 1930s. Iacob and Fritz sit in the woods and smile, relaxed, into the camera. The viewer’s eyes can pass over the branches and leaves from a safe distance, lose themselves in the thicket of trees, and trace the contours of the petrified bodies of the king and the mermaid. Maximilian made these images with a video camera; the video beamer casts them onto the screen. One’s innocence returns; here is a world without time.

In the anniversary issue of the magazine “Frauen und Film”(“Women and film”), Heide Schlüpmann describes how the silent-movie star Asta Nielsen acted beyond cinematic narration: “Nielsen acts frontally and energetically and often positions herself in the foreground. With her posture in the film, she is already thinking about her appearance in the space of the movie theater, and, in a mixture of isolation and vigorous revelation, she empathetically addresses an audience that also tends toward isolation at the same time as its yearning for closeness drives it into the cinema: an audience that, arrived there, lets itself fall into a darkness whose joys are governed by the apparatus, the projector.”

Nielsen, “coming from gender-politically progressive Denmark – and yet with her self-confidence unprotected in life and in the theater” – is successful at a time when private life, says Schlüpmann, is detached from the life of the state. It finds asylum in the cinema, the place where body and soul, especially those of women, are permitted to be. At the same time, the cinema arises as an architectural site, as a building positioned in both the urban space and the cultural landscape – though it has difficulties finding its place in the latter.

“Heaven, I’m in heaven,” it resounds after the union. Iacob and Fritz dance. In love, passionately wrapped in each other’s arms, they seem to float, but against the logic of gravity: some of their odd postures ought to make them fall. Then it becomes clear: Iacob and Fritz are lying on the ground, the camera suspended above them. It is not they who are in heaven, but the viewer, who is looking downward, as in a kinetoscope, the1888 predecessor of the endless-loop installation. Except that Maximilian’s Darkroom is not directed vertically downward, but horizontally. The viewer is upright, as are the two dancers.

Schlüpmann describes how Nielsen’s appearance meets a longing for closeness that the star cannot fulfil. Still, her work is not deceitful (like that of advertisements) since cinema, as an institution of the private within the public, allows intimacy.

In the catalogue “X-Screen – Filmische Installationen und Aktionen der Sechziger- und Siebziger Jahre” (“X-Screen – filmic installations and actions of the 1960s and ‘70s”), Birgit Hein describes in a similar way, but somewhat more pointedly (and thus shifting from the realm of the erotic to that of the sexual), Tapp- und Tastfilm (“groping and feeling film”) by Valie Export, in which passers-by/viewers could stick not their heads, but their hands, into a box that was built much like Quirynen’s peepshow. By feeling the filmmaker’s naked breasts, they could experience not a sham satisfaction, but a genuine one, albeit limited by the fact that they were being observed. Similarly, a Berlinale audience member walks onto the stage in Maximilian’s Darkroom and becomes an actor in a performance (one that has occurred long ago).

Film material was initially at the center of Birgit Hein’s filmwork (Rohfilm, together with Wilhelm Hein); later it was her own body, at first with film performances, and finally in films themselves (from Love Stinks to Baby I Will Make You Sweat). The route that led filmmaker Birgit Hein and her contemporaries in the 1960s and ‘70s from fine arts through film and performance and back to the art business describes nothing less than the integration of the body into the architectonic space, which itself becomes an expression of media. The video artist Anne Quirynen has always worked with dancers, performers, and musicians, among whom she counts herself (Maximilian) as well as the viewer Maximilian. Her body, in the hierarchy just as much a site of recording as the video camera and just as much a source of projection as the video beamer, functions as the cinematic apparatus, the darkroom. The latter’s inside and outside, the before and after of this architecture, form the idea of the screen, mirrored in the face of the viewer.

In the 1960s and ‘70s, expanded cinema actions, performances, and multiple projections served to reinvent a cinema that takes body and space into account. Like the actress Asta Nielsen, who made the coordinates of film her own by appearing, the expanded cinema artists made the body a component of the technical recording and projection apparatus. Anne Quirynen’s video installation permeates the cinema with its historicity and underscores what it can do best: abducting the viewer not only in his head, but in his whole corporeality to absent places and distant times. It seduces him to new identities. In this lies the genuine queerness of cinema and its installation: its stories have never proceeded linearly and have always happened in places that could also be situated at the rear of the movie house.

Biofilmography

Anne Quirynen was born in 1960 in Sint-Niklaas, Belgium. She works as a video artist in Berlin and teaches video installation at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and European Media Science at the Academy Potsdam.

Installations: The Mindmachine of Dr. Forsythe (1993), Everything will be allright (1997, both together with Peter Missotten and An-Marie Lambrechts), Jetzt (Now; 2000), In a Landscape (2001), Interzone (2004).

Films: 1997: The Way of the Weed (full-length feature film). 2001: In a Landscape.

Here you can find the complete version of the text :

Maximilian’s Darkroom.pdf

show less